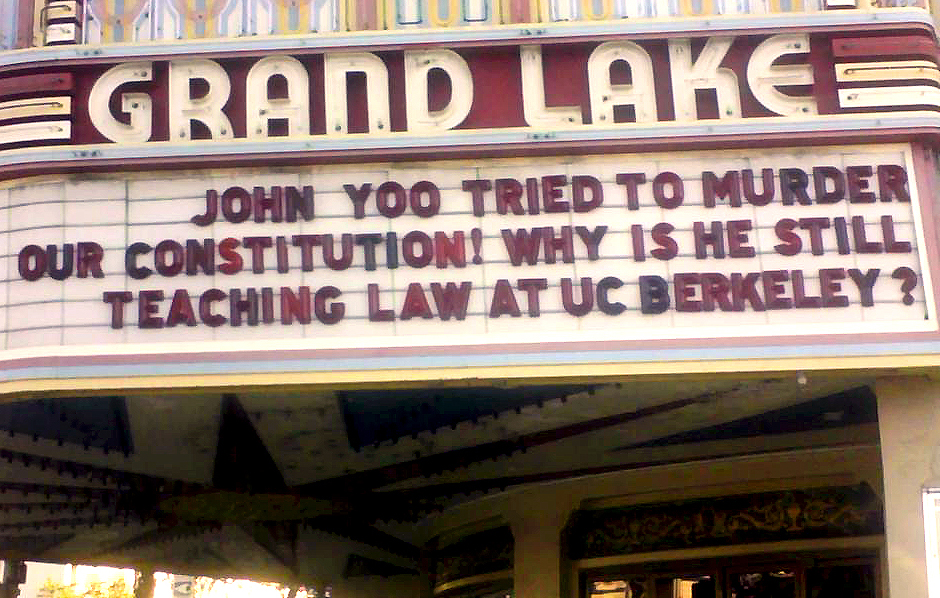

The demand that John Yoo be fired, disbarred, and tried as a war criminal (along with other Bush administration lawyers and officials) has provoked fierce controversy among some legal academics, who are unfortunately viewing this case far too narrowly and seeing it as a threat to tenure and academic freedom--an attempt to punish a faculty member for his ideas, however repugnant they may be viewed. Some opposing it have made comparisons to the unjust firing last July of tenured Professor Ward Churchill* by the

* Churchill will participate in a debate at Stanford University, "Western Civilization: Oppression or Emancipation?" Thursday, October 16:

7:00 PM - 9:00 PM

Arrillaga Alumni Center

362 Galvez St.

Palo Alto

But there is no basis to compare the right-wing witch hunt that targeted Churchill solely for his controversial statements written after 9/11 and used them to get him fired, with the call for Yoo's ouster and prosecution.3 The firing of Churchill is part of an intense assault on academic freedom and critical thinking spearheaded by reactionary forces, like David Horowitz, who are closely connected to high-level ruling class forces. As CCR President Michael Ratner wrote in the forthcoming book The Trial of Donald Rumsfeld, these memos authored by Yoo were not just academic exercises. "They were written by high-level attorneys in a context where the opinions represented the governing law and were to be employed by the President in setting detainee policy. This was more than bad lawyering; this was aiding and abetting their clients' violation of the law by justifying the commission of a crime using false legal rhetoric."

It would be wrong to call for Yoo's firing if he were simply a right-wing academic who had written and voiced very reactionary and repugnant views (in the course of academic work, or in other settings), even endorsing torture. Someone like that should be challenged in debates, but firing a professor for their views should be opposed. But Yoo is not just an academic with controversial ideas. As a key member of the Bush regime's legal team, he was someone who was actively involved in legalizing torture and other horrors.

Another argument that has support is one made by Boalt Hall Dean Christopher Edley, Jr. in his statement opposing the demand to dismiss Yoo. Dean Edley, himself having been in and out of White House positions twice in the past, asserts that there exists a "complex, ineffable boundary between policymaking and law-declaring." He argues that Yoo's conduct in giving legal advice was not morally equivalent to the actions of Rumsfeld, or of the Guantánamo interrogators. Yes, says Edley, "it does matter that Yoo was an adviser, but President Bush and his national security appointees were the deciders."

But there is precedent for prosecuting lawyers who have played this kind of advisory role in laying the legal groundwork for subsequent crimes. As a part of the

Philippe Sands, in his new book Torture Team: Rumsfeld's Memo and the Betrayal of American Values, writes, "The charge [in the "Justice Cases"]... was that men who had been leaders of the German legal system had 'consciously and deliberately suppressed the law' and contributed to crimes, including torture, that 'were committed in the guise of legal process.'" The prosecutor in the case had argued that "Men of law can no more escape responsibility by virtue of their judicial robes than the general by his uniform."

Yet as it stands today in this country both the "generals in their uniforms" and the "men in their judicial robes" continue to escape responsibility for their crimes--past, present, and in the planning. The fact they have not yet been held accountable has nothing to do with their culpability...