Time Magazine

Monday, November 3, 2008

by Johnny Dwyer

As the curtain falls on the Bush Administration, one set piece of the Administration's policy on torture has finally been ushered offstage. The Bybee Memo, a 2002 opinion authored by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, was brushed aside last week by a federal judge overseeing the nation's first-ever criminal trial of an American accused of torture abroad. The public defenders representing torture suspect Chucky Taylor, a U.S. citizen and the son of former Liberian military strongman Charles Taylor, submitted it for consideration as part of potential jury instructions. But Federal Judge Cecilia Altonaga rejected the terms laid out in the memo, saying, "I will not give an instruction that relies upon that memorandum as its authority."

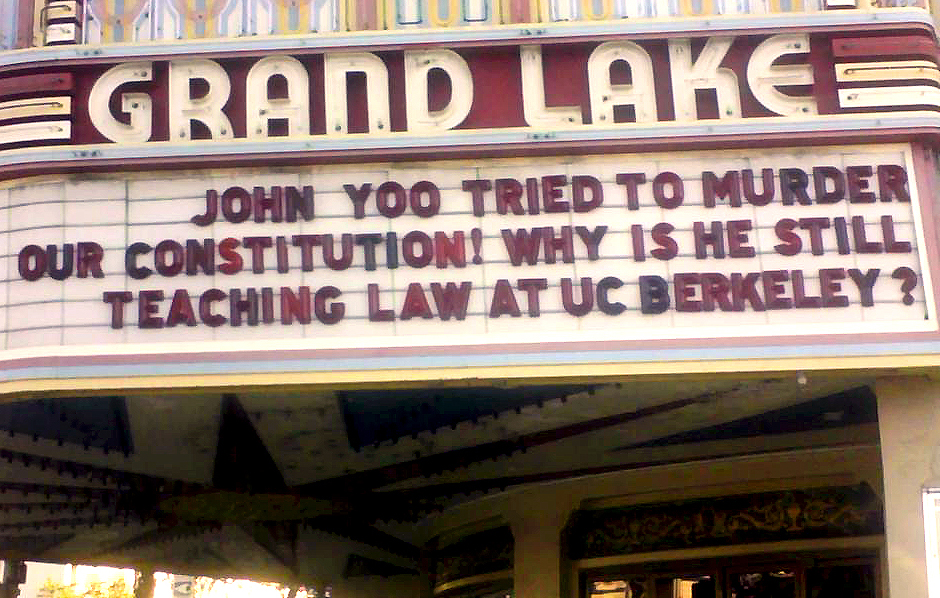

It was a humiliating epilogue to the Bush Administration's attempt to integrate what many critics describe as undeniable torture into U.S. military and intelligence policy. The Bybee memo, (named for Jay Bybee, then head of the Office of Legal Counsel) was largely authored by John Yoo, then Deputy Assistant Attorney General of the Office of General Counsel. It provided legal guidance for civilians engaged in interrogating terrorism suspects. Administration officials feared that CIA employees and other nonmilitary personnel could face indictment under the federal law that upholds U.S. obligation to the United Nations Convention Against Torture. The memo narrowly defined torture as an act "equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death."

From the outset, critics of the memo viewed the legal thinking behind it as flawed. Then Navy general counsel Alberto Mora identified it as a "dangerous document" that "spots some of the legal trees, but misses the constitutional forest. Because it identifies no boundaries to action -- more, it alleges there are none -- it is virtually useless as guidance." What particularly troubled Mora and other critics of the memo was that, as a document from the Office of Legal Counsel, its opinions were binding as the Administration's interpretation of the law.

Continue reading Bush Torture Memo Slapped Down by Court.

Monday, November 3, 2008

by Johnny Dwyer

Activists demonstrate "water boarding" technique during a protest in front of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Mark Wilson / Getty

As the curtain falls on the Bush Administration, one set piece of the Administration's policy on torture has finally been ushered offstage. The Bybee Memo, a 2002 opinion authored by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, was brushed aside last week by a federal judge overseeing the nation's first-ever criminal trial of an American accused of torture abroad. The public defenders representing torture suspect Chucky Taylor, a U.S. citizen and the son of former Liberian military strongman Charles Taylor, submitted it for consideration as part of potential jury instructions. But Federal Judge Cecilia Altonaga rejected the terms laid out in the memo, saying, "I will not give an instruction that relies upon that memorandum as its authority."

It was a humiliating epilogue to the Bush Administration's attempt to integrate what many critics describe as undeniable torture into U.S. military and intelligence policy. The Bybee memo, (named for Jay Bybee, then head of the Office of Legal Counsel) was largely authored by John Yoo, then Deputy Assistant Attorney General of the Office of General Counsel. It provided legal guidance for civilians engaged in interrogating terrorism suspects. Administration officials feared that CIA employees and other nonmilitary personnel could face indictment under the federal law that upholds U.S. obligation to the United Nations Convention Against Torture. The memo narrowly defined torture as an act "equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death."

From the outset, critics of the memo viewed the legal thinking behind it as flawed. Then Navy general counsel Alberto Mora identified it as a "dangerous document" that "spots some of the legal trees, but misses the constitutional forest. Because it identifies no boundaries to action -- more, it alleges there are none -- it is virtually useless as guidance." What particularly troubled Mora and other critics of the memo was that, as a document from the Office of Legal Counsel, its opinions were binding as the Administration's interpretation of the law.

Continue reading Bush Torture Memo Slapped Down by Court.