Excerpts from Scott Horton's Justice After Bush: Prosecuting An Outlaw Administration in Harper's Magazine.

This administration did more than commit crimes. It waged war against the law itself. It transformed the Justice Department into a vehicle for voter suppression, and it also summarily dismissed the U.S. attorneys who attempted to investigate its wrongdoing. It issued wartime contracts to substandard vendors with inside connections, and it also defunded efforts to police their performance. It spied on church groups and political protestors, and it also introduced a sweeping surveillance program that was so clearly illegal that virtually the entire senior echelon of the Justice Department threatened to (but did not in fact) tender their resignations over it. It waged an illegal and disastrous war, and it did so by falsely representing to Congress and to the American public nearly every piece of intelligence it had on Iraq. And through it all, as if to underscore its contempt for any authority but its own, the administration issued more than a hundred carefully crafted "signing statements" that raised pervasive doubt about whether the president would even accede to bills that he himself had signed into law.

No prior administration has been so systematically or so brazenly lawless. [...] Indeed, in weighing the enormity of the administration's transgression against the realistic prospect of justice, it is possible to determine not only the crime that calls most clearly for prosecution but also the crime that is most likely to be successfully prosecuted. In both cases, that crime is torture.

There can be no doubt that torture is illegal. There is no wartime exception for torture, nor is there an exception for prisoners or "enemy combatants," nor is there an exception for "enhanced" methods. The authors of the Constitution forbade "cruel and unusual punishment," the details of that prohibition were made explicit in the Geneva Conventions ("No physical or mental torture, nor any other form of coercion, may be inflicted on prisoners of war to secure from them information of any kind whatever"), and that definition has in turn become subject to U.S. enforcement through the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the U.S. Criminal Code, and several acts of Congress. [...]

Nor can there be any doubt that this administration conspired to commit torture: Waterboarding. Hypothermia. Psychotropic drugs. Sexual humaliation. Secretly transporting prisoners to other countries that use even more brutal techniques. The administration has carefully documented these actions and, in many cases, proudly proclaimed them. [...]

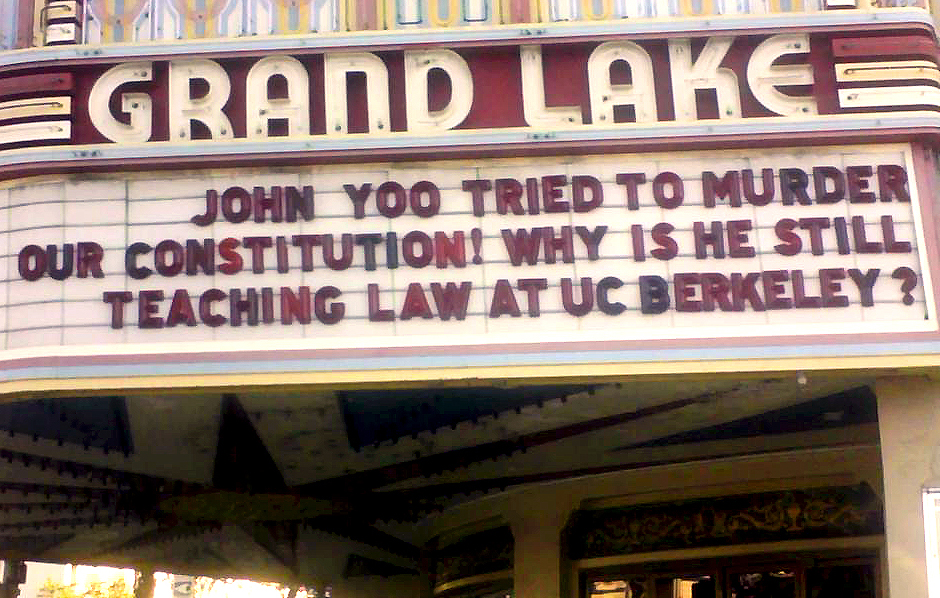

Finally, there can be no doubt that the administration was aware of the potential criminality of these acts. In January 2002, White House lawyers began generating a series of memos outlining the administration's motivation for torturing. They claimed that "the war against terrorism is a new kind of war" requiring an enhanced "ability to quickly obtain information from captured terrorists" and that "this new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva's strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners." [...]

Waterboarding is far from the worst that detainees have suffered under U.S. supervision. Its use is especially worthy of note, however, because it is universally understood that 1) the administration authorized waterboarding, and 2) waterboarding is a serious crime. [...]

Open criminality is a cancer on democracy. It implicates all who know of the conduct and fail to act. Such compliance presents a practical crisis, in that a government that is allowed to torture will inevitably transgress other legal limits. [...][This] ha[s] little to do with a perceived benefit from the use of torture in interrogation. To the contrary, the very criminality of the act ha[s] a talismanic difference. It assert[s] the primacy of the will of the torturer. It ma[kes] a claim, for all to accept or reject, that the ruler is the law. [...]

Reasserting the rule of law is no simple matter. A new administration may--or may not-- bring an end to open torture in the United States, but it will not bring an end to our knowledge and acceptance of what has already taken place. If the people wish to maintain sovereignty, they must also reclaim responsibility for the actions taken in their name. As of yet, they have not. Pursuing the Bush Administration for crimes long known to the public may amount to a kind of hypocrisy, but it is a necessary hypocrisy. The alternative, simply doing nothing, not only ratifies torture; it ratifies the failure of the people to control the actions of their government. [...]

This administration did more than commit crimes. It waged war against the law itself. It transformed the Justice Department into a vehicle for voter suppression, and it also summarily dismissed the U.S. attorneys who attempted to investigate its wrongdoing. It issued wartime contracts to substandard vendors with inside connections, and it also defunded efforts to police their performance. It spied on church groups and political protestors, and it also introduced a sweeping surveillance program that was so clearly illegal that virtually the entire senior echelon of the Justice Department threatened to (but did not in fact) tender their resignations over it. It waged an illegal and disastrous war, and it did so by falsely representing to Congress and to the American public nearly every piece of intelligence it had on Iraq. And through it all, as if to underscore its contempt for any authority but its own, the administration issued more than a hundred carefully crafted "signing statements" that raised pervasive doubt about whether the president would even accede to bills that he himself had signed into law.

No prior administration has been so systematically or so brazenly lawless. [...] Indeed, in weighing the enormity of the administration's transgression against the realistic prospect of justice, it is possible to determine not only the crime that calls most clearly for prosecution but also the crime that is most likely to be successfully prosecuted. In both cases, that crime is torture.

There can be no doubt that torture is illegal. There is no wartime exception for torture, nor is there an exception for prisoners or "enemy combatants," nor is there an exception for "enhanced" methods. The authors of the Constitution forbade "cruel and unusual punishment," the details of that prohibition were made explicit in the Geneva Conventions ("No physical or mental torture, nor any other form of coercion, may be inflicted on prisoners of war to secure from them information of any kind whatever"), and that definition has in turn become subject to U.S. enforcement through the Uniform Code of Military Justice, the U.S. Criminal Code, and several acts of Congress. [...]

Nor can there be any doubt that this administration conspired to commit torture: Waterboarding. Hypothermia. Psychotropic drugs. Sexual humaliation. Secretly transporting prisoners to other countries that use even more brutal techniques. The administration has carefully documented these actions and, in many cases, proudly proclaimed them. [...]

Finally, there can be no doubt that the administration was aware of the potential criminality of these acts. In January 2002, White House lawyers began generating a series of memos outlining the administration's motivation for torturing. They claimed that "the war against terrorism is a new kind of war" requiring an enhanced "ability to quickly obtain information from captured terrorists" and that "this new paradigm renders obsolete Geneva's strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners." [...]

Waterboarding is far from the worst that detainees have suffered under U.S. supervision. Its use is especially worthy of note, however, because it is universally understood that 1) the administration authorized waterboarding, and 2) waterboarding is a serious crime. [...]

Open criminality is a cancer on democracy. It implicates all who know of the conduct and fail to act. Such compliance presents a practical crisis, in that a government that is allowed to torture will inevitably transgress other legal limits. [...][This] ha[s] little to do with a perceived benefit from the use of torture in interrogation. To the contrary, the very criminality of the act ha[s] a talismanic difference. It assert[s] the primacy of the will of the torturer. It ma[kes] a claim, for all to accept or reject, that the ruler is the law. [...]

Reasserting the rule of law is no simple matter. A new administration may--or may not-- bring an end to open torture in the United States, but it will not bring an end to our knowledge and acceptance of what has already taken place. If the people wish to maintain sovereignty, they must also reclaim responsibility for the actions taken in their name. As of yet, they have not. Pursuing the Bush Administration for crimes long known to the public may amount to a kind of hypocrisy, but it is a necessary hypocrisy. The alternative, simply doing nothing, not only ratifies torture; it ratifies the failure of the people to control the actions of their government. [...]