Are US Officials Guilty of War Crimes?by

Andy Worthington

Will

the Bush administration be held accountable for war crimes? The answer

ought to be yes, if the verdict of the Senate Armed Services Committee

Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in US Custody is to mean

anything. The bipartisan report, released on December 11 by senators

Carl Levin and John McCain, concluded that the torture and abuse of

prisoners was the direct result of policies authorized or implemented

by senior officials within the current administration, including

President George W. Bush, former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and

Vice President Dick Cheney's former legal counsel (and now chief of

staff) David Addington.

Since

the scandal of the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq

broke in April 2004, over a dozen investigations have identified

problems concerning the treatment of prisoners in Iraq, Afghanistan and

Guantanamo, but until now no official report has looked up the chain of

command to blame senior officials for authorizing torture and

instigating abusive policies. The Bush administration has been able to

maintain, as it did in the wake of the Abu Ghraib scandal, that any

abuse was the result of the rogue activities of "a few bad apples."

This

is now untenable. As the report states: "The abuse of detainees in US

custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of 'a few bad

apples' acting on their own. The fact is that senior officials in the

United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive

techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their

legality, and authorized their use against detainees. Those efforts

damaged our ability to collect accurate intelligence that could save

lives, strengthened the hand of our enemies, and compromised our moral

authority."

Though containing

little new information, the report is damning in its revelation of how

senior officials sought out and approved the reverse engineering of

techniques taught in the US military's SERE schools (Survival, Evasion,

Resistance, Escape) for use on prisoners captured in the "war on

terror." These include "stripping detainees of their clothing, placing

them in stress positions, putting hoods over their heads, disrupting

their sleep, treating them like animals, subjecting them to loud music

and flashing lights, and exposing them to extreme temperatures." In

some circumstances, the measures also included waterboarding, a

notorious torture technique which involves controlled drowning.

After

noting that these techniques were taught to train personnel "to

withstand interrogation techniques considered illegal under the Geneva

Conventions," and that they are "based, in part, on Chinese Communist

techniques used during the Korean war to elicit false confessions," the

authors laid out a compelling timeline for the introduction of the

techniques, beginning with a crucial memorandum issued by Bush on

February 7, 2002. This stated that the protections of the Geneva

Conventions, which the authors noted "would have afforded minimum

standards for humane treatment," did not apply to prisoners seized in

the "war on terror."

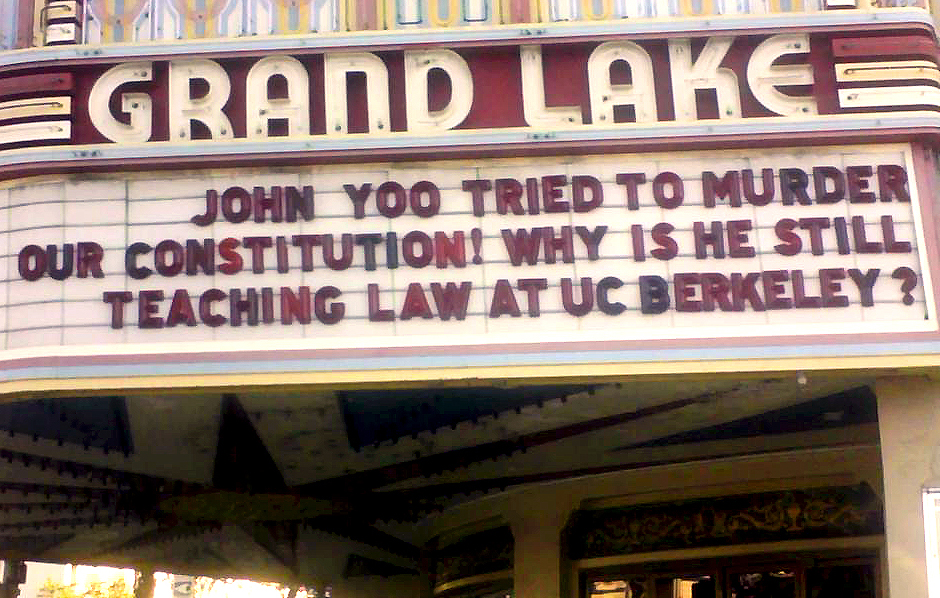

Having

established Bush's role as the initial facilitator of abuse, the report

then implicated those directly responsible for implementing torture,

explaining how Pentagon general counsel William J. Haynes II began

soliciting advice from the agency responsible for SERE techniques in

December 2001, and how Addington, Justice Department legal adviser John

Yoo, and White House counsel Alberto Gonzales attempted to redefine

torture in the notorious "Torture Memo" of August 2002. The memo

claimed that the pain endured "must be equivalent to the pain

accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment

of bodily function, or even death."

The

authors also noted how Rumsfeld approved the use of SERE techniques at

Guantanamo in December 2002 (after Haynes had consulted with other

senior officials), and explained how the techniques migrated to

Afghanistan in January 2003, and were implemented by Lieutenant General

Ricardo Sanchez, the commander of coalition forces in Iraq, in

September 2003.

Even so,

the report is not without its faults. The authors carefully refrained

from ever using the words "torture" or "war crimes," which is a

considerable semantic achievement, but one that does little to foster a

belief that the officials involved will one day be held accountable for

their crimes. They also, curiously, omitted all mention of Vice

President Dick Cheney, and ignored the importance of the presidential

order of November 2001, which authorized the capture and indefinite

detention of "enemy combatants," even though Barton Gellman of The

Washington Post has established that Cheney played a significant role

in this and all the other crucial documents that led to the torture and

abuse of detainees.

Responses

in the US media have been mixed. Oddly, most major media outlets chose

to focus solely on Rumsfeld's responsibility for implementing abusive

techniques. More thoughtful commentators have questioned whether Barack

Obama would pursue those responsible, noting that he will be unwilling

to antagonize Republicans, whose support he needs to tackle the

economic crisis, and that many Democrats in Congress knew about the

administration's policies, and in some cases were involved in approving

them. A recent article in The Nation noted that such complicity made

"an unfettered review seem unlikely," but the article also noted, more

hopefully: "A growing body of legal opinion holds that Obama will have

a duty to investigate war crimes allegations and, if they are found to

have merit, to prosecute the perpetrators."

As

of December 17, those concerned with pursuing Bush administration

officials for war crimes can at least be assured that the perpetrators

now include Cheney. In an interview with ABC News, the vice president

stuck to a now-discredited script, declaring "we don't do torture, we

never have," but admitted for the first time that he knew about the use

of waterboarding on a handful of "high-value detainees," and that he

considered its use in their cases "appropriate."

Only

time will tell if Cheney's admission will be regarded as a stalwart

defense of national security, or as the last defiant gesture of a war

criminal.

The onetime Bush Attorney General admitted Tuesday that "skittish" law firms won't hire him after his departure under fire from the Justice Department surrounding his role in the political firings of nine US Attorneys. He says he considers himself a victim of the "war on terror," though his firing actually came after what seemed to be a war on US Attorneys who didn't cleave to Administration policies.

The onetime Bush Attorney General admitted Tuesday that "skittish" law firms won't hire him after his departure under fire from the Justice Department surrounding his role in the political firings of nine US Attorneys. He says he considers himself a victim of the "war on terror," though his firing actually came after what seemed to be a war on US Attorneys who didn't cleave to Administration policies.

Â View Larger Image

View Larger Image