Edge of dictatorship

Two years ago, my son Peter gave me a book entitled "The End of America." Its author, Naomi Wolf, issued a warning of how a dictator could take over our country "by invoking emergency decrees to close down civil liberties; creating military tribunals; and criminalizing dissent." Wolf described the "echoes" of such events in America. She made a plausible case that it could happen here. But when I read the book, I did not think so.

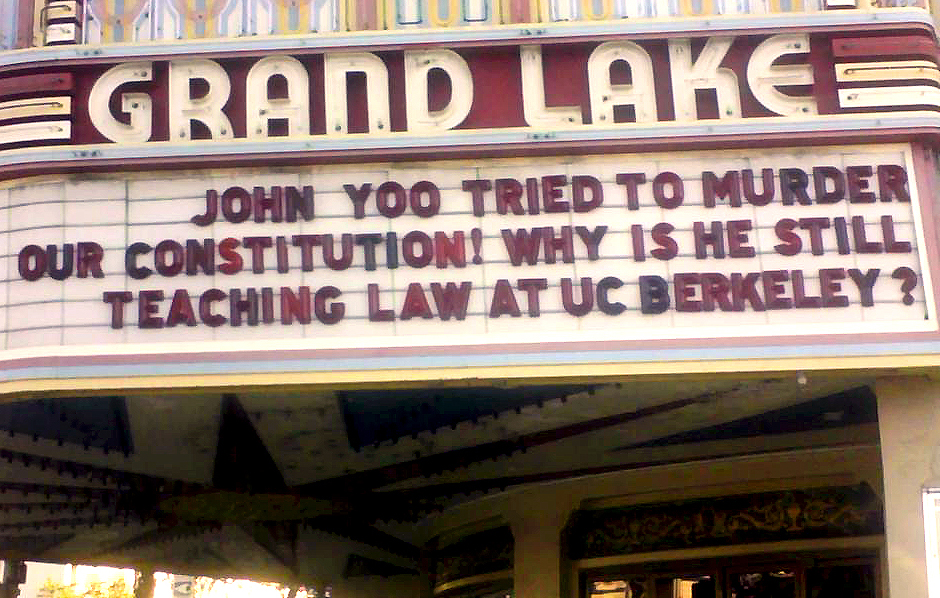

I had second thoughts when I found out that the groundwork was being laid for it to happen here by the "torture memos" written by John Yoo, a Justice Department lawyer in the Office of Legal Counsel (OCL) for former President George W. Bush. And I was shocked that all it would take is a government lawyer's made-to-order legal opinion, no matter how flawed, to a president bent on exercising dictatorial powers.

John Dean, a former counsel to President Nixon, recently referred to such legal opinions as "corporate lawyer opinions." Those are written for corporate heads who order them from their lawyers to fit a corporate decision and never mind the legal fine points.

Bush and members of his administration decided to use torture, including waterboarding, which in an Orwellian euphemism they called an "enhanced" method of interrogating suspected terrorists to obtain information. They also sought a legal opinion from their Justice Department's OLC to cover themselves from criminal prosecution.

The U.S. criminalizes acts of torture inside the country by state and federal criminal laws for assault, battery, murder, and so on. It specifically criminalizes "torture," defined as the intentional infliction of severe pain and suffering, physical or mental, outside of the country, by federal law and by the ratification of a U.N. Convention Against Torture and the Geneva Conventions, which prohibited the torture of prisoners of war. Apart from the common sense knowledge that the drowning sensation produced by waterboarding is torture as that term is commonly understood, there is a well-established legal precedent for this meaning. Japanese interrogators who used this method on American prisoners of war were convicted as war criminals.

Alberto R. Gonzales, as a lawyer and former judge, knew or should have known that waterboarding was torture and punishable as a crime based on the common understanding of the word "torture" and the clarity of the law, treaties and legal precedent dealing with it. Yet, he, as Bush's legal counsel, requested an opinion in 2002 from the OLC regarding whether Bush's enhanced interrogation methods of al-Qaida suspects during the "current war on terrorism" violated international law, and if these methods could be the basis for prosecution in the International Criminal Court. The only reasonable explanation for the request of this opinion is that the Bush administration wanted a legal cover against future prosecution.

They got it in Yoo's "torture memos." These legal opinions were full of his personal views and lacked any court cases, constitutional text and American history on point. Yoo noted that torture, as a crime, required a specific intent to inflict severe pain and suffering, but in his bizarre reasoning, he concluded this was not the intent of the interrogators. They, according to Yoo, intended only to obtain information and any pain or suffering was incidental to their objective. Therefore, he concluded, Bush's "enhanced" method of interrogation was not the crime of torture punishable under U.S. law and the U.N. treaty. A first year law school student would get an F for such obviously flawed legal reasoning.

In dealing with the Geneva Conventions protection of prisoners of war, Yoo without any pretense of research or precedents, simply declared that al-Qaida suspects in custody were not prisoners of war because they were members of "non-state terrorists organizations that have not signed (the) Convention." In other words, they were individuals, like those under a dictatorship, without any legal rights or protection.

Then Yoo went further in his memos and declared that in his view of the Constitution, the president as commander-in-chief during a war (Bush's war on terrorism) has broad powers and any ambiguities, constitutional or otherwise, are to be resolved in favor of full presidential power.

President Obama's administration recently released more of these memos by Yoo and others which justified the president's violation of the constitutional Bill of Rights. These memos reportedly would allow the use of the military in America to break into homes and take away suspected "illegal combatants" and hold them indefinitely without a court hearing, spy on Americans without court orders, and stifle speech by cracking down on critics.

Just five days before Obama's inauguration, Bush's acting head of OLC, Steven Bradbury, whose name reportedly appears on some of these memos, disavowed them by saying they were flawed and no longer supported by that office. The Justice Department's Office of Professional Responsibility has reportedly prepared a highly critical report of Yoo and the memos.

The chilling thought is that if Bush fully acted on these memos, would our other democratic institutions (the legal system, other elected officials) have stopped him? Wolf points out that such institutions in Germany in the 1930s could not stop the dictatorship there.

Robert "Frank" Jakubowicz, a Pittsfield lawyer, is a regular Eagle contributor.