In Torture Cases, Obama Toes Bush Line

Legal Stance Appears to Contradict Earlier Statements From Obama and Holder

While Congress debates whether senior Bush administration officials should be called to account for the torture, humiliation and indefinite detention of prisoners taken during the "war on terror," some of those prisoners aren't waiting around for lawmakers to make up their minds. A growing number of private lawsuits brought by former detainees against former Bush officials are slowly making their way through the courts. And to the dismay of some of its strongest supporters, the Obama administration has, in every case so far, taken the side of the Bush administration, arguing that these cases should all be dismissed.

What's more, Obama administration lawyers are not arguing for dismissal purely on procedural grounds. In most cases, they're arguing that the courts should not second-guess the president's authority in national security matters. They are also insisting that the right to not be tortured, to be treated humanely and to not be detained indefinitely without charge or trial were not clearly established back when government officials violated them. Therefore, under the legal doctrine of "qualified immunity," those officials should not be held responsible now, the Justice Department claims.

That stance outrages many of the lawyers handling these cases. "Torture has always been illegal," said Eric Lewis, a partner in the law firm Baach Robinson & Lewis, which is representing four British former Guantanamo detainees against former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld. "Affirming qualified immunity for torture seems contrary to the traditions of the military which abjure torture and contrary to the doctrine of qualified immunity which says you are protected within a large discretionary area," but not for acts that were clearly illegal. "It can't be right that prior to Boumediene" -- the landmark Supreme Court case affirming Guantanamo prisoners' rights to challenge their detention in U.S. courts -- "anyone could have thought that torture was legal," said Lewis.

Lewis is among a group of formidable opponents the administration faces in these cases, including some of the nation's top lawyers and law schools making powerful legal arguments that former government officials are legally responsible for the torture, abuse and wrongful imprisonment that their policies directed.

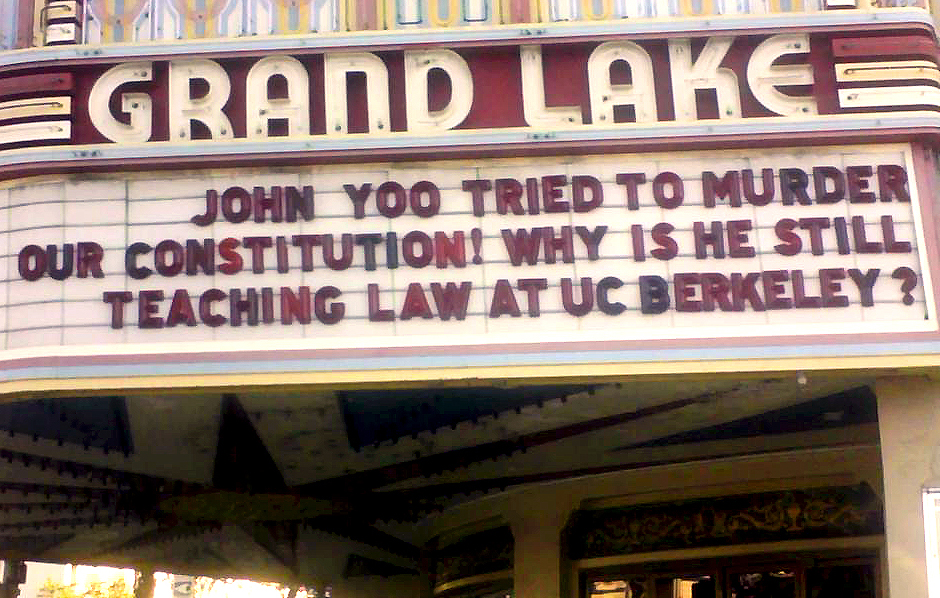

In a federal court in San Francisco this month, for example, lawyers from Yale Law School'sLowenstein International Human Rights Clinic argued that John Yoo, the deputy assistant attorney general at the Office of Legal Counsel during the Bush administration and author of several memos that effectively gave legal cover for U.S. authorities to torture prisoners, is now liable for the consequences of his legal advice.

The lawyers represent Jose Padilla, the U.S. citizen who was declared an enemy combatant and held for three years without charge or trial at a Navy brig in South Carolina. Padilla's lawyers claim he was subjected to "vicious interrogations, chilling sensory deprivation and total isolation." And they claim that John Yoo is responsible because he not only provided the legal justification for that treatment but, as a member of the Bush "War Council," helped develop the administration's interrogation policy.

"Yoo knew exactly what the natural consequences of his actions would be - because he intended them, because they were obvious, and because he was warned by others," the lawyers write in their brief opposing the government's motion to dismiss the case.

The Obama administration, stepping into the shoes of its predecessors, has now assumed the awkward position of arguing that the case against Yoo -- whose opinions Obama administration officials have harshly criticized -- should be dismissed. The Obama Justice Department is arguing that Yoo, as a government lawyer, was not directly responsible for decisions regarding Padilla's treatment; that allowing such legal claims against a government official would "constitute an unprecedented intrusion into the President's authority in the areas of war-making, national security and foreign policy"; and that Yoo did not violate "any clearly established constitutional rights."

The Obama administration is making a very similar argument in another case, Rasul v. Rumsfeld, now pending at the United States Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit. In that case, four British citizens who were abducted in Afghanistan and sent to Guantanamo Bay claim they were imprisoned in cages, brutally beaten, shackled in painful stress positions, forced to shave their beards and watch their Korans desecrated. They were finally released in 2004 without charge. They have sued former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld and other senior Pentagon officials for their treatment.

The case was dismissed at the urging of the Bush administration, but appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court. In December, the court sent it back to the court of appeals in Washington for reconsideration in light of the Supreme Court's landmark ruling last summer in Boumediene v. Bush that Guantanamo detainees have the right to challenge their detentions.

Rumsfeld, former Attorney General John Ashcroft and other former senior Bush officials also face a similar case brought by the Yale law clinic in South Carolina, where Padilla was being held. Because Yoo lives in California, he was sued separately in his home state to avoid potential jurisdictional problems.

Meanwhile, another torture damages case, Arar v. Ashcroft, involving a Canadian citizen abducted in New York and sent abroad to be tortured, is pending before the Second Circuit Court of Appeals. Still other lawsuits, such as one filed by Khaled al-Masri, a former detainee allegedly held and tortured by the CIA for five months in Afghanistan, has been dismissed based on government arguments that all information about the case and the CIA program al-Masri was subjected to is a "state secret" that the government may not be forced to disclose. (Other victims of so-called "extraordinary rendition" -- or transfer to torture -- are now suing the private flight data company that assisted the CIA in the hopes of getting around that problem, though as TWI has written, the Obama administration is maintaining -- as the Bush administration did before it -- that the "state secrets doctrine" should ban those suits as well.)

Many more such cases could still be filed: the Detainee Abuse and Accountability Project has documented more than 330 cases in which U.S. military and civilian personnel are credibly alleged to have abused or killed detainees. Other detainees released from Guantanamo have told reportersthat they are considering bringing lawsuits.

Victims Want an Accounting

The lawyers representing former prisoners say money is usually not the motive in these cases; rather, their clients want the government to acknowledge that the harsh and humiliating treatment they endured was wrong, and to clear their names from the stigma of years in a military prison. Jose Padilla and his mother, for example, are only asking for $1 from John Yoo. "Plaintiffs seek to vindicate their constitutional rights," their legal complaint says, "and ensure that neither Mr. Padilla nor any other person is treated this way in the future."

The stigma and continued suffering of former Guantanamo prisoners is highlighted in a thoroughreport published in November from the University of California at Berkeley. Researchers studied 62 former Guantanamo detainees and found that, having been labeled "the worst of the worst" by the U.S. government, they "left Guantánamo shrouded in 'guilt by association,' particularly as their innocence or guilt had never been determined by a court of law." This "Guantánamo stigma" made it difficult to find jobs and reintegrate into their communities. Many had severe physical and mental health problems, but could not afford treatment. And as the report emphasizes: "To date, there has been no official acknowledgment of any mistake or wrongdoing by the United States as a result of its detention or treatment of any Guantánamo detainee. No former detainees have been compensated for their losses or harm suffered as a result of their confinement."

President Obama has carefully avoided saying whether he would support either prosecutions of Bush officials or a non-prosecutorial truth commission, as proposed by Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.). And as TWI has reported, proposals for broad investigatory commissions have so far not won a majority of supporters in Congress. These private lawsuits therefore may provide the only means of finding out how the government developed and carried out its detention and interrogtion policies, and their impact on individual prisoners.

Still, they face significant hurdles. Even if former prisoners can prove that the officials they've sued developed and authorized the policies that led to their treatment, federal officials can usually win lawsuits involving work they did in government by claiming "qualified immunity."

Under the doctrine of "qualified immunity," federal government officials cannot be sued for actions taken in office unless they were intentionally violating clearly established rights. Lawyers for the former detainees claim that the right not to be tortured, brutalized, humiliated, held indefinitely without charge and denied religious freedoms is well-established in American and international law. The Bush administration, however, consistently denied that.

Now, much to the chagrin of many Obama supporters, the Obama administration is claiming the same thing. The administration "should not be arguing that there was not a clearly established right to be free from detention without trial, court access or abuse under the Fifth and Eighth amendments," said Michael Ratner, president of the Center for Constitutional Rights and a professor at Columbia Law School, and co-counsel on the Rasul case. That's "a grave disappointment" and would "justify many of the nasty Bush administration practices."

The position also seems to contradict earlier statements from President Obama and Attorney General Eric Holder. On the campaign trail, for example, Obama said about torture: "When I am president America will once again be the country that stands up to these deplorable tactics. When I am president we won't work in secret to avoid honoring our laws and Constitution, we will be straight with the American people and true to our values." At his confirmation hearing, Holder said unequivocally that "waterboarding is torture" and that "the president does not have the power" to authorize torture.

Now, to make the case that former Bush officials have "qualified immunity," the attorney general is arguing that the law was actually not so clear just a few years ago.

While this may be the best legal defense these officials have, the contradictions could be putting the Obama administration in an ethical bind. While it's not unusual for a subsequent administration to defend lawsuits filed against the previous one, lawyers usually try to refrain from arguing positions in one case that contradict their stance in another.

Then again, the Obama administration's position in these cases is consistent with at least some positions it has taken in other recent matters regarding detainees and "enemy combatants." For example, in moving recently to dismiss the habeas corpus petition of Ali Saleh Kahlah al-Marri, a U.S. resident held for six years in the same South Carolina Navy brig as Padilla before recently being transferred to federal prison, the Obama administration notably did not relinquish his "military combatant status" or the right to hold lawful U.S. residents indefinitely without charge or trial on U.S. soil.

And on Friday, although the Obama administration announced that it would stop using the term "enemy combatant," it insisted that it maintains the right to hold indefinitely without charge or trial anyone that the president declares assisted al Qaeda or the Taliban. It's not clear what the administration plans to call such prisoners now.

Legal Outcome is Uncertain

So do the prisoners suing the former government officials have a chance?

"So long as Yoo acted solely as a lawyer giving advice to his own client in good faith, even wrong advice, he will not be liable to those denied their constitutional rights, even if the denial is a direct result of the bad advice," said Stephen Gillers, professor of legal ethics at New York University Law School. But many critics believe -- based on the memos from the Office of Legal Counsel that have been released so far, on statements from former Bush administration officials such as Jack Goldsmith, who took over OLC and later denounced many of Yoo's memos, and on Yoo's role in Bush's "war council" -- that Yoo was not providing objective, good-faith legal advice. Rather, they claim he distorted the law to justify the actions the White House wanted to take. If true, that could cause Yoo legal problems. "If Yoo stepped out of his role as a lawyer and distorted his advice in order to facilitate the harsh interrogation and other conduct," said Gillers, "then he loses this professional immunity and is liable along with others for their violation of constitutional rights."

A still-classified internal report drafted by the Office of Professional Responsibility in the Department of Justice reportedly analyzes the memos regarding interrogation and detention produced by the Office of Legal Counsel during the Bush administration, and examines whether the authors of the memos, including Yoo, purposely slanted their legal advice to provide President Bush and other high-level policymakers with the the conclusions they wanted.

As for the government's argument that the court should not second-guess the judgments of policymakers making decisions about national security, Lewis, co-counsel on the Rasul case, insists that some decisions should be subject to review. "They argue that you don't want government officials doing their job with the threat of liability hanging over them," said Lewis, whose firm is handling the case pro bono. "But one would think that the threat of liability for torturing people is something you'd want to put in there as a disincentive."

To be sure, some legal experts believe the court should stay away from judging policymaking, whether the ultimate policies applied turned out to be legal or not. "If we're talking about holding a particular individual liable, we're talking about drawing a straight line between opinions given and acts done," said Daniel Richman, a professor at Columbia University law school. "At the end of the day people who really were hurt by the government in ways that are legally offensive ought to have some sort of forum to get compensation or vindication. But to go from there to say that part of that process should involve singling out one or two subpresidential actors in an area where the president really does dominate policymaking is a stretch for me."

As I've written before, a broad investigatory commission, of the sort proposed by Rep. John Conyers (D-Mich.) or Sen. Leahy could provide a means for torture victims to receive government reparations, as truth commissions frequently do in other countries, creating a more efficient alternative to these individual lawsuits.

Although it's impossible to predict what will happen in any of these cases, District Court Judge Jeffrey White, hearing arguments in Padilla's case against Yoo earlier this month, seemed to at least take the claims against Yoo very seriously. Yoo's recently released opinion concluding that the president can override the Fourth Amendment's protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, he reportedly said, is "a pretty scary position."

Jonathan Freiman, a lawyer with the Yale law school clinic representing Padilla, noted that dismissing the case would be disturbing for another reason. "We've seen the policymakers trying to get out of things saying we were just relying on legal advice," said Freiman. "Now the lawyers are trying to get out of things saying we were just giving legal advice, not making policy decisions. So in this view of things no one is ever responsible for anything."

Indeed, former Attorney General Michael Mukasey, former Vice President Dick Cheney and others in the Bush administration insisted that there was no need for criminal investigations of policymakers because all of them had been relying on the advice of legal counsel. If it turns out the advice of legal counsel was merely dictated by the policymakers, though, then maybe none of them will get off so easy.