Eric Holder must decide whether to pursue Bush administration lawyers and one sitting federal judge who set the legal stage for officially sanctioned torture and other degrading practices that violated fundamental principles of international law. As Mr. Holder wrestles with this decision, he must consider the gold standard set by his predecessor Robert Jackson at Nuremberg.

As World War II drew to a close and the defeat of Nazi Germany became certain, leaders debated what to do with the Nazis. The Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin, argued that 50,000 German general staff officers should be executed.

In February 1945 at the Yalta Conference, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill favored shooting all the Nazi leaders. In April, French Gen.Charles de Gaulle came out in favor of a trial. The British continued to push for summary executions.

After President Harry Truman took office, he opposed executions and supported the idea of creating an international tribunal to try the war criminals. Soon after Italian leader Benito Mussolini was shot and German leader Adolf Hitler committed suicide, the United States assumed leadership in the creation of a new international court to "expand international penal law beyond the traditional limits of the laws of war."

On May 2 Truman appointed Robert Jackson as chief counsel to prepare the indictment of the Nazi leaders for atrocities and war crimes. Jackson felt strongly that it had to be scrupulously fair. "You must put no man on trial before anything that is called a court if you are not willing to see him freed if proven not guilty."

His opening statement set the tone for the trials:

"That four great nations, flushed with victory and stung with injury, stay the hand of vengeance and voluntarily submit their captive enemies to the judgment of the law is one of the most significant tributes that Power has ever paid to reason.... We must summon such detachment and intellectual integrity to our task that this trial will commend itself to posterity as fulfilling humanity's aspirations to do justice."

Most, but not all, of the 21 defendants were convicted.

Some observers say that US government employees who carried out acts that the United States had previously called torture (when done by employees of other governments) should be left in peace because they were following orders.

But Holder should recall the testimony of William Keitel, the ranking officer of the German Army: "I took the stand that a soldier has a right to have confidence in his state leadership, and accordingly he is obliged to do his duty and to obey." The Nuremberg tribunal sentenced Keitel to death by hanging.

Article 8 of the London Charter that established the Nuremberg court made clear that obedience to an order from a superior to commit a crime is not a defense but can be considered only in mitigation of punishment. Since Nuremberg, following orders has ceased to be a valid defense in international law. Until 2001, the United States firmly and rightly adhered to that standard.

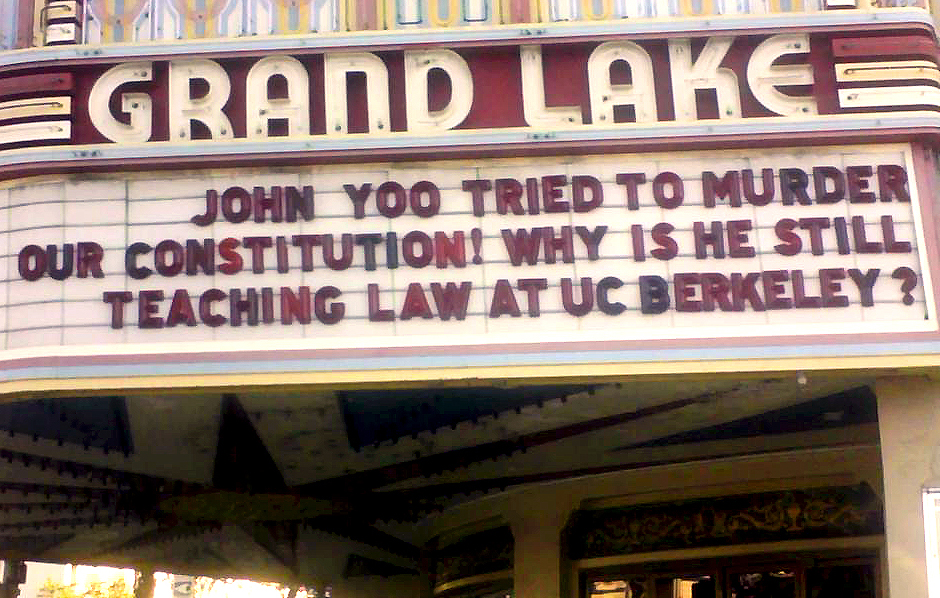

If the rule of law is to have any meaning at all, then lawyers must function within accepted boundaries of the legal discipline. Those boundaries are very large, but they are not unlimited.

The lawyers Holder may pursue advised President Bush that the Geneva Conventions and the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, ratified by the American government, could be ignored. They further argued that acts that America had in the past called torture had now miraculously ceased to be torture. Such positions put those advisers well outside even the furthest boundaries.

Some acts are morally wrong and cannot be defended. Neither an order from a superior nor a Justice Department opinion can transform such an act into one that is morally right. Water boarding is but one example.

There cannot be a set of legal rules applicable to other nations and citizens but to which America need not adhere. To regain its moral legitimacy, American must formally recognize that some of its official post-9/11 practices were unlawful.

A truth commission composed of Americans and non-Americans would help assure that the inquiry would be fair and free of political grandstanding. There is good precedent by the Carnegie Foundation. In the 1940s to the Swedish economist Gunnar Myrdal studied the American race problem.Myrdhal's report proved influential when the US Supreme Court came to rule on school segregation in 1954.

That there will be a day of historical reckoning is beyond doubt. In France the reckoning took 50 years. In 1995 President Jacques Chirac formally and belatedly acknowledged "the dark hours that sullied our history and injured our traditions" admitting that the French Vichy regime government was complicit in World War II atrocities. The issue is how quickly it will come. The attorney general must find the courage to face it now.

Ronald Sokol is a member of the bar in the United States and in France. He practices in Aix-en-Provence. He is the author of "Justice After Darwin" and other books and articles.