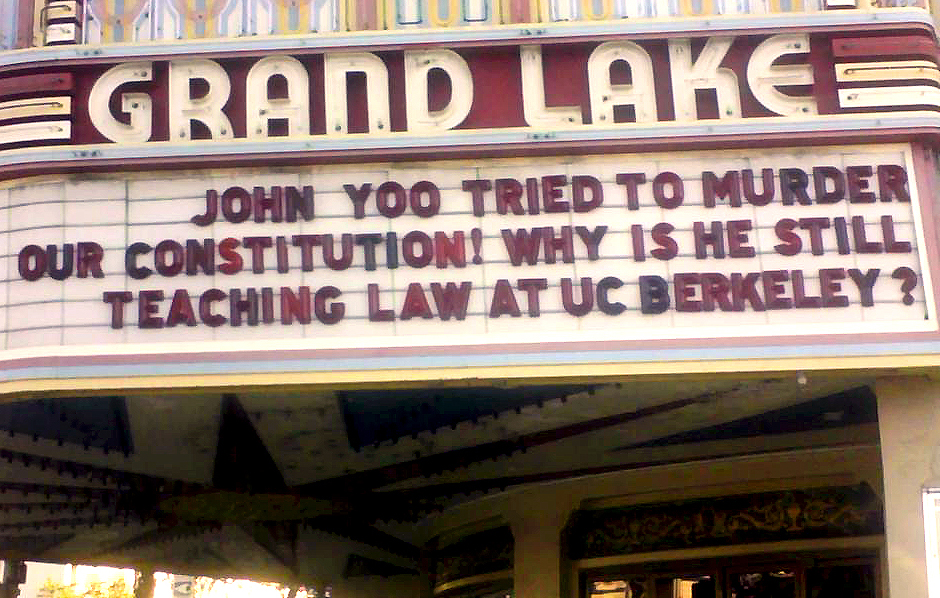

Protesters want professor fired

By TERENCE CHEA

Associated Press Writer

Photo by Noah Berger

BERKELEY, California | Anti-war activists protested Monday at the University of California, Berkeley to call for the firing of a law professor who co-wrote legal memos that critics say were used to justify the torture of suspected terrorists during the Bush administration.

BERKELEY, California | Anti-war activists protested Monday at the University of California, Berkeley to call for the firing of a law professor who co-wrote legal memos that critics say were used to justify the torture of suspected terrorists during the Bush administration.Campus police arrested at least four people who refused to leave the university's law school building.

The demonstrators said John Yoo should be dismissed, disbarred and prosecuted for war crimes for his work as a Bush administration attorney from 2001 to 2003, when he helped craft legal theories for waterboarding and other harsh interrogation techniques.

Shouting "war criminal," the protesters confronted Yoo as he entered a lecture hall on the first day of class at UC Berkeley's Boalt Hall School of Law, where the tenured professor is teaching a civil law course this semester.

Yoo mostly ignored the demonstrators and waited for police to remove them from the classroom before he began teaching. Several officers then stood outside the lecture hall to prevent protesters and journalists from entering.

Demonstrators also staged a mock arrest of Yoo. Some dressed in black hoods and orange prisoner suits similar to ones seen in infamous photos of Iraq's Abu Ghraib prison, which was closed in 2006 following reports of detainee abuse. The Iraqi government reopened the prison with a new name in February.

"There is little doubt that John Yoo is a war criminal," said civil rights attorney Dan Siegel, speaking outside Boalt Hall. "John Yoo went to Washington and created the ideological, political and legal basis for the torture of innocent people."

Yoo, who returned to UC Berkeley after spending the spring semester at Chapman University School of Law in Orange County, did not immediately respond to requests for comment Monday.

Yoo, 42, has defended the controversial interrogation techniques, saying they were needed to protect the country from terrorists after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

"To limit the president's constitutional power to protect the nation from foreign threats is simply foolhardy," Yoo wrote in a Wall Street Journal opinion piece last month.

He has come under intense criticism since the interrogation memos became public in 2004. The Berkeley City Council has passed a measure calling for the federal government to prosecute him for war crimes, and convicted terrorist Jose Padilla has filed a lawsuit alleging that Yoo's legal opinions led to his alleged torture.

Christopher Edley Jr., Berkeley's law school dean, has rejected calls to dismiss Yoo, saying the university doesn't have the resources to investigate his Justice Department work, which involved classified intelligence.

Berkeley law students are divided over Yoo, whose classes are among the law school's most popular.

Liz Jackson, a second-year law student, said the university should determine if he violated UC's faculty code of conduct. "I personally believe he has blood on his hands," said Jackson, 30.

But Nathan Salha, 24, who took one of Yoo's classes last year and is enrolled in his course this semester, said he's a good teacher. "I don't think it's the university's place to fire him for political opinions," he said.