Two investigating judges from the Spanish national security court, the Audiencia Nacional, are asking the U.S. Justice Department for details about the role played by Bush Administration lawyers in the development and approval of torture practices that were apparently applied to a number of Spanish subjects held in Guantanamo.

The judges have asked for responses by the end of October, setting up another major test for Attorney General Eric Holder. This time, the question is whether Holder will choose to oblige or stymie international criminal investigations of Bush officials for torture, in the absence of any domestic efforts in that direction...

see also Spanish Judge Presses Ahead With Lawsuit Against Bush Lawyers

Holder has thus far threaded the needle between torture critics and torture apologists by launching a narrowly tailored preliminary inquiry into a small group of incidents that exceeded Justice Department guidances in place at the time.

Had he launched a more wide-ranging investigation, the Spaniards would almost certainly have abandoned theirs, which is based on the principle of universal jurisdiction when it comes to such things as war crimes.

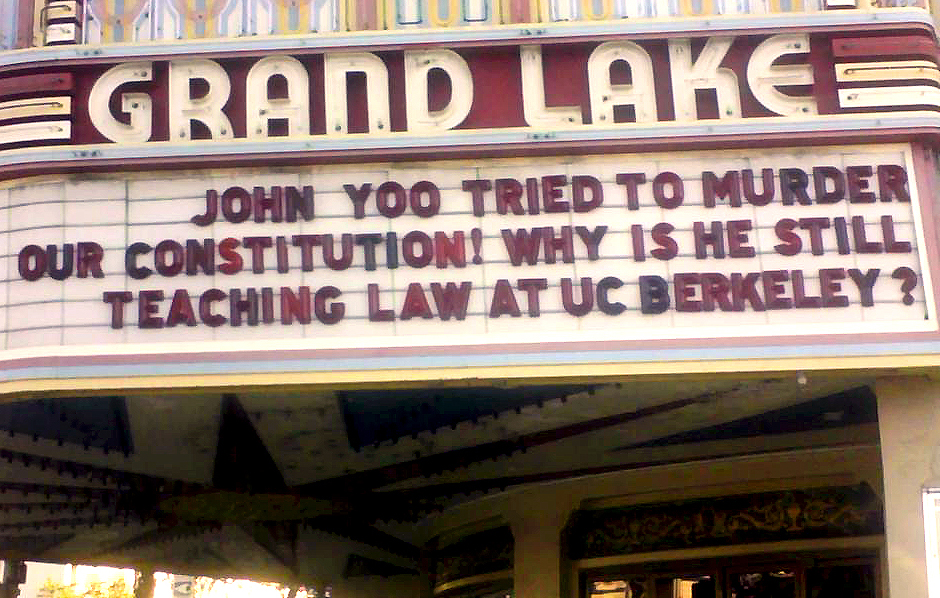

The Spanish authorities are deciding whether to continue with a criminal investigation targeting the so-called Gonzales Six -- former attorney general Alberto Gonzales; former Justice Department officials Jay Bybee (now a judge on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals) and John Yoo (now a law professor in Berkeley, California); David Addington, the former chief of staff to vice president Cheney; former undersecretary of Defense for Planning Douglas Feith, and former defense department general counsel William J. Haynes II (now a lawyer with Chevron).

The two separate cases involve Judges Eloy Velasco and Baltasar Garzon and arise out of related facts -- one coming of out of a complaint brought by a Spanish human rights organization on behalf of abused Spanish nationals held at Guantanamo, the other stemming from a failed effort by Judge Garzon to prosecute those same prisoners. A conviction initially secured by Judge Garzon was overturned in a later decision of the Spanish Supreme Court, which found substantial evidence that the prisoners had been tortured. The Spanish Supreme Court labeled Guantanamo a "legal black hole," forbade Spanish prosecutors to rely on evidence secured by American interrogators there and directed a more detailed investigation into the prisoner's claims that they had been tortured.

In the course of the last week, I interviewed a number of figures involved in these two cases in Madrid, including lawyers practicing before the Audiencia Nacional and court investigators, in order to get a sense of their likely trajectory. I learned that the two judges were closely monitoring developments in the United States, and particularly Holder's decision to appoint career prosecutor John Durham to conduct a preliminary inquiry into a group of ten or more incidents in which the CIA's inspector general concluded that the conduct of CIA interrogators exceeded the guidelines they were given by the Justice Department.

Under Spanish law, the opening of a criminal investigation covering the same matters by the United States would probably lead to the termination or suspension of a case in Spain grounded on universal jurisdiction. However, the Spanish authorities tentatively concluded that suspension of their cases was not warranted at this point because Holder had placed so many limitations on Durham's work and because it does not appear that Durham is being asked to examine the cases involving the Spanish subjects who were held at Guantanamo.Â

Judges Garzon and Velasco are also clearly focusing their inquiries on the roles played by the Gonzales Six, whereas Holder appears to have structured the Durham probe to limit any investigation into the role that Justice Department lawyers and others played in the matter. The Spanish authorities will probably reassess if the Durham preliminary review leads to a more formal criminal investigation. If they conclude that Durham is also examining the potential culpability of the Gonzales Six, that would likely lead to a suspension of the Spanish proceedings.

The Spanish investigators are now hoping for detailed responses to the questions they sent the U.S. Justice Department in the form of "letters rogatory" -- the customary method of obtaining judicial assistance from abroad in the absence of a treaty or executive agreement. The questions focus on the treatment of the Spanish subjects held at Guantanamo and the specific authority and approval for that treatment. They also probe in more detail into the role played by Gonzales, Bybee and Yoo in the process, reflecting a view that the U.S. Justice Department was itself the locus of much of the criminal conduct connected to introduction of a system of torture and cruel treatment of Spanish subjects, in violation of the Spanish criminal code using its universal jurisdiction arm.

The government of Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Zapatero, which has held confidential discussions with the Obama Administration, has strongly opposed the inquiries. Spanish Attorney General Candido Conde-Pumpido, a member of Zapatero's cabinet, instructed his representatives attached to the Audiencia Nacional to seek their termination. On April 17, Conde-Pumpido gave a press conference at which he ridiculed suggestions that attorneys could face any liability for torture, saying that only those who were present in the room when the torture occurred faced liability. However, in Spain, unlike the United States, criminal investigations are pursued not by the attorney general and his staff, but by judges who are independent of political structures. Neither of the two judges has, so far, agreed with Conde-Pumpido's position. Moreover, his analysis of potential liability for torture was squarely rejected in one interim decision of the court, which concluded that legal culpability for torture rested principally with the "intellectual authors" of the program, rather than those who administered the program.

The Zapatero government, with support from its political opposition, recently steered legislation through the Spanish parliament modifying Spain's universal jurisdiction statute to limit the sorts of foreign cases that the Audiencia Nacional could handle. The legislative change does not, however, affect the proceedings involving the Gonzales Six, since cases in which Spanish subjects are victims of torture remain within the core competence of the court, regardless of where the acts of torture occurred or whatever other governments may have been involved.

On Saturday, the Spanish newspaper El Publico reported that Judge Garzon had agreed to expand his case by admitting a number of human rights organizations and a political party as parties who would have a right of participation in any trial. Huffington Post blogger Andy Worthington offered a summary of the Publico piece with some updates.

It is unclear how the Holder Justice Department will react to the Spanish court's request. Lawyers attached to the Audiencia Nacional state that during the Bush years, the U.S. Justice Department was not forthcoming in answering requests for information, even with respect to counterterrorism prosecutions the Spanish undertook with U.S. prompting. Holder, noting that this concern was broadly expressed by European law enforcement authorities, has pledged in several appearances in Europe to introduce a new spirit of cooperation with the European on counterterrorism matters. However, the case of the Gonzales Six presents an unusual challenge since former personnel from the Justice Department are clearly in the prosecutorial cross-hairs.

Spanish authorities expressed particular puzzlement over Holder's decision not to release a study prepared by the Department's Office of Professional Responsibility that looks into the conduct of Yoo, Bybee and their successor, Steven G. Bradbury. This report has been five-years in the making. "This report probably contains a good deal of the information that is being sought in the interrogatories," one court investigator told me.

British law professor Philippe Sands, whose expert testimony was a key factor in the Audiencia Nacional's initial decision to accept the case involving the Gonzales Six, takes the view that the Spanish cases will now go forward. Sands told me:

The effect of Mr Holder's important first decision to appoint a special prosecutor on a limited number of cases involving the CIA means that there will not be, for the time being at least, any sort of investigation (as required by the Torture Convention), of the real authors of the abuse, including the lawyers. Ironically, the decision means that those who made implicit threats with drills that were never used may be investigated, whereas those who authorized, ordered or carried out waterboarding, sexual humiliation, stress positions and the use of dogs will not be. Hardly a logical approach, and not exactly consistent with the scheme under the Convention.That's a bright green light for continued foreign investigations. I have no doubt that the DoJ will, in due course, do the right thing and respond to the letters rogatory. What the response might contain, however, is a matter of some interest.

For the moment, however, the attention is focused on the U.S. Justice Department. Will it treat the Spanish criminal investigation seriously? Or will it continue the Bush Administration's practice of turning a cold shoulder to any such queries? It is, yet again, a question of change versus continuity.

About Scott Horton

Scott Horton is a contributing editor at Harper's Magazine, where he writes on law and national security issues, an adjunct professor at Columbia Law School, where he teaches international private law and the law of armed conflict, and a frequent contributor to the Huffington Post. A life-long human rights advocate, Scott served as counsel to Andrei Sakharov and Elena Bonner, among other activists in the former Soviet Union. He is a co-founder of the American University in Central Asia, where he currently serves as a trustee. Scott recently led a number of studies of issues associated with the conduct of the war on terror, including the introduction of highly coercive interrogation techniques and the program of extraordinary renditions for the New York City Bar Association, where he has chaired several committees, including, most recently, the Committee on International Law. He is also an associate of the Harriman Institute at Columbia University, a member of the board of the National Institute of Military Justice, Center on Law and Security of NYU Law School, the EurasiaGroup and the American Branch of the International Law Association and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations. He co-authored a recent study on legal accountability for private military contractors, Private Security Contractors at War. He appeared at an expert witness for the House Judiciary Committee three times in the past two years testifying on the legal status of private military contractors and the program of extraordinary renditions and also testified as an expert on renditions issue before an investigatory commission of the European Parliament.