Stance Follows Presidential Declaration That Torture Is Illegal

When he took office, President Obama made clear that torture is illegal and that the United States would not abuse detainees in its custody. He immediately ordered the CIA as well as the rest of the U.S. government to adhere to the rules set out in the Army Field Manual, which forbid the torture, abuse or humiliation of prisoners.

But when it comes to those tortured during the Bush administration, the Obama administration refuses to say that Bush officials violated existing law. In fact, in litigation over the torture and abuse of detainees that in some cases may have resulted in their deaths, the Obama administration has surprisingly endorsed the same legal positions as its predecessor, insisting that there is no constitutional right to humane treatment by U.S. authorities outside the United States, and that victims of torture and abuse and their survivors have no right to compensation or even an acknowledgment of what occurred.

Several cases making their way through the courts now are challenging that position. In each, the Obama administration is taking essentially the same legal positions as did the Bush Justice Department before it.

The case of Al-Zahrani v. Rumsfeld, brought on behalf of two former Guantanamo detainees found dead in their cells in June 2006, is among the most recent filed. It's now being actively litigated in a Washington, D.C. federal court. Neither Yasser Al-Zahrani nor Salah Al-Salami was ever charged with a crime, but both were deemed "enemy combatants" by a Defense Department procedure that the Supreme Court later declared inadequate. They spent four years in U.S. custody at Guantanamo Bay without charge, without seeing the evidence against them, and without ever even meeting with a lawyer who could press their case. On June 10, 2006, the men were found hanged in their cells on a rope made from bed sheets and T-shirts. The military declared both deaths suicides. Al-Zahrani was 17 years old when he was transferred to Guantanamo and 22 when he died. Al-Salami died at age 37.

In January, the men's fathers sued Defense Department officials. Represented by the Center for Constitutional Rights and the Human Rights Law Clinic at Washington College of Law at American University, the fathers claim their sons were subjected to conditions and treatment that the International Red Cross has described as "tantamount to torture." They also claim that Defense Department officials ignored obvious signs of their deteriorating mental health, their growing despair, and the high risk of suicide.

In letters found after their deaths, the two prisoners described being beaten, deprived of sleep for up to 30 days, held in freezing cold or excruciatingly hot temperatures, subjected to humiliating and degrading body searches, prevented from practicing their religion, forcibly shaved contrary to their religious beliefs, and denied necessary medication. Both men were also isolated from the outside world and their families, and even separated from other detainees. According to their lawyers, they "spent the majority of each day confined alone in a small cell with numbingly little activity or stimuli and deprived of basic personal care items." Al-Zahrani, who was one of the first detainees to arrive at Camp X-Ray in Guantanamo Bay, was held for the first few months of his detention in a small wire cage.

To protest their detention and conditions, the two men, along with dozens of other detainees, went on a hunger strike for several months. The government responded not by improving the conditions, but by restraining the men in chairs, forcing tubes down their noses and throats, and pumping food into their stomachs, their lawyers claim.

Meanwhile, they argue, it was clear that the prisoners' mental health was deteriorating. In August 2003, nearly two dozen prisoners tried to hang themselves in their cells. And according to the complaint filed in this case, a military official acknowledged that shortly before the deaths of Al-Zahrani and Al-Salami, there was a high risk of mass suicide in the prison.

The relatives filed their lawsuit against 24 military officials, including former Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Gen. Richard Myers, seeking acknowledgment of wrongdoing and compensation for the two prisoners' deaths. But in June, the Obama administration's Justice Department moved to dismiss the case. The government's lawyers argued, among other things, that the Military Commissions Act, passed by Congress in 2006, had stripped the federal courts of jurisdiction over claims challenging the "detention, transfer, treatment, or conditions of confinement" of detainees who were considered "enemy combatants" by the U.S. military and detained abroad.

Although lawsuits were brought during the Bush administration similarly suing Bush military officials for abuse, wrongful imprisonment and torture, none of those cases involved detainees who the military had decided were "enemy combatants." But a slew of cases were brought on behalf of so-called "enemy combatants" seeking review of the legality of their detention in federal court.

In one of those cases decided last year, the Supreme Court held that part of that provision of the Military Commissions Act was an unconstitutional suspension of the right of habeas corpus, which allows a prisoner to challenge his detention. But that case, Boumediene v. Bush, did not rule specifically on whether prisoners have the right to challenge the conditions of their detention or their treatment in prison. The decision pertained solely to the right to challenge the detention itself.

Now, for the first time, the lawyers representing the families of Al-Zahrani and Al-Salami are arguing that the part of the Military Commissions Act that deprived the courts of hearing challenges to the treatment of detainees and conditions of their confinement is unconstitutional as well, and that Congress lacked the authority to strip the federal courts of jurisdiction over constitutional claims.

"Article III [of the U.S. Constitution] demands some federal court review--whether original or appellate--over all federal question claims," writes the Center for Constitutional Rights in its brief to the D.C. federal court filed last week. "Because MCA Section 7 purports to eliminate all such review, it is unconstitutional and void."

As CCR lawyer Shayana Kadidal explained it in an e-mail: "the text of Article III of the Constitution (the article dealing with the judicial branch) expressly says 'the judicial power shall extend to all cases' involving questions of federal law." The Military Commissions Act contradicts that, says Kadidal: "The MCA says no court anywhere can review even constitutional claims."

The Obama administration is insisting, however, that Congress had the power to eliminate judicial review of these claims. It also argues that the Defense Department officials are immune from suit, because, as the Bush Justice Department argued in previous cases, it wasn't clear at the time that detainees had a right not to be tortured by U.S. officials at Guantanamo. They therefore have "qualified immunity" from suit.

But the Justice Department goes further than that. Under President Obama, the government is arguing not only that it wasn't clear what rights detainees were entitled to back in 2006, but that even today the prisoners have no right to such basic constitutional protections as due process of law or the right to be free from cruel and unusual punishment. The "Fifth and Eighth Amendments do not extend to Guantánamo Bay detainees," writes the Justice Department in its brief.

And, the government argues, the courts should not imply a right to sue under the Constitution, in part because that could lead to "embarrassment of our government abroad."

Ultimately, the Obama administration is arguing, victims of torture at a U.S.-run detention center abroad have no right to redress from the federal government. Only the military can take action in such cases, by disciplining military officers for abuse of prisoners. Yet during the Bush administration, military officials were rarely held accountable for abuse, even when it resulted in the deaths of detainees, as Human Rights First documented in a 2005 report. Senior officials in particular were exempt from accountability, and as retired Rear Admiral John Hutson, dean of the Franklin Pierce Law Center, noted at the time, "the highest punishment for anyone handed down in the case of a torture-related death has been five months in jail."

TWI has also documented that the Pentagon has repeatedly ignored claims from its own military counsel that Defense Department employees abused, tortured and committed war crimes against detainees, as in the case of Guantanamo prisoner Mohammed Jawad.

Pardiss Kebriaei, the lead attorney on the case for the Center for Constitutional Rights, insists that the government is misreading Supreme Court precedent when it comes to the rights of Guantanamo detainees. "The Supreme Court has ruled three times that Guantanamo is not beyond the reach of the law, yet the government is claiming, in 2009, that the base is still a legal black hole and what happens at Guantanamo stays at Guantánamo," said Kebriaei.

Eric Lewis, who represents four British former detainees who sued the federal government for their wrongful imprisonment and torture while in custody, and whose case was dismissed under the Bush administration (they recently filed a petition for review by the Supreme Court,) thinks the parents of Al-Zahrani and Al-Salami have a strong argument that the part of the law that strips the courts of jurisdiction over their claims is unconstitutional.

"If there's a constitutional right, you need to provide some forum," he said. "You can't deprive them of all forums."

Although the government officials are also claiming immunity on the grounds that they didn't know it was unconstitutional to torture prisoners, Lewis argues that in the Al-Zahrani case, unlike earlier ones, there's a case to be made that by 2006, when the men died, the Supreme Court had already ruled in Rasul v. Bush that detainees have the constitutional right to challenge their detention at the Guantanamo Bay prison camp, where the U.S. has "plenary and exclusive jurisdiction" even if it doesn't have "ultimate sovereignty." In other words, the court had already ruled that Guantanamo detainees have some constitutional rights.

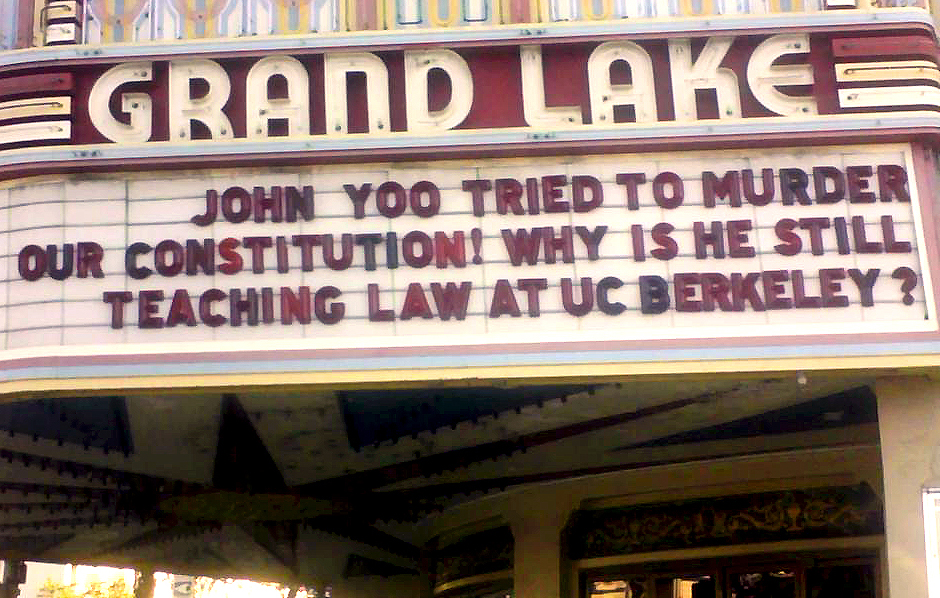

The government, for its part, argues that it still wasn't clear what specific rights Guantanamo detainees were entitled to, even in June 2006. And that argument could prevail. As Richard Seamon, a professor at the Idaho School of Law who has written extensively about torture lawsuits notes in a recent article posted on JURIST, federal officials in such cases may be granted qualified immunity "because of the paucity of case law clearly establishing the unconstitutionality of the use of torture in the war on terrorism and high-level executive-branch actions seemingly endorsing the torture, such as the Department of Justice's infamous 'torture memo.'"

Then again, as Lewis put it: "I would argue that when you're the secretary of defense, you don't need special notice to know it's wrong to torture people."

According to the Justice Department's latest briefs filed in the Al-Zahrani case, however, the Obama administration does not agree.