This decade's so-called war on terrorism included many legal missteps: the designation of prisoners as "enemy combatants" and the determination that the Geneva Conventions didn't apply to them; the creation of a legal black hole at Guantanamo and the military commissions slapped together to try prisoners there.

But the worst were the "torture memos," written by Bush administration lawyers at the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel to fudge the rules for prisoner interrogations. The memos represent the lowest low point in post-9/11 legal thought. They were proof that in wartime, the law is as malleable as the most cynical lawyer.

Dahlia Lithwick, senior editor at Slate Magazine and Reihan Salam, fellow at the New American Foundation, will be online Monday, Dec. 21 at 11 a.m. ET to discuss the worst ideas of the decade... go here.

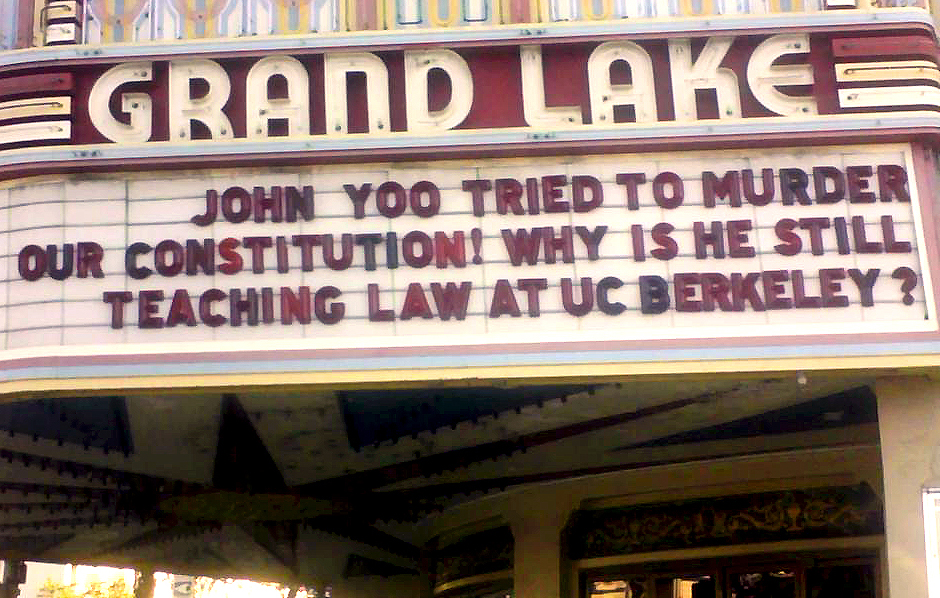

The August 2002 memo, reportedly written by John Yoo and signed by Jay Bybee, started it all. It redefined "severe pain or suffering" by cherry-picking language from a health benefits statute to argue that "severe" pain must be "equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death." The same memo said that interrogators could avoid legal liability by claiming "self-defense" and "necessity," and that they were not criminally liable for torture if they acted at the behest of the president. Trussed up in lofty language and what passed for legal reasoning, the memos gave legal cover to brutal prisoner abuse that had come before and that would come later.

Without any evidence that torture was either necessary or effective, the memos made it possible for prisoners to suffer abuse and even death. These memos were generated in a post-9/11 panic, of course, when the administration feared new attacks and could not get new intelligence fast enough. But in the end, the conduct so cavalierly authorized was neither helpful in producing relevant information nor legal.

Whatever dangers American troops now face abroad because this country briefly authorized torture are the responsibility of the memos' authors. These documents represent the moment at which conscientious lawyers would have said "no," but when Bush lawyers instead seemed to have asked, "Would you like a soda with that, Mr. President?" As legal scholar David Cole recently observed, "If OLC lawyers had exercised independent judgment and said no to the CIA's practices, as they should have, that might well have been the end of the Bush administration's experiment with torture." Because they said yes, America became a nation that tortured, and a nation that may torture again.