http://tinyurl.com/mlgbpj

Meanwhile in a second case in the 9th Circuit Court, the Obama administration has increased its defense of secrecy surrounding an alleged CIA program of torture flight, http://www.sfgate.com/cgi-bin/

The Obama administration, under pressure to turn over key memos written by the Justice Department's Office of Legal Counsel, has asked the federal judge in New York for another 90 days to consider its position on a Freedom of Information Act case brought by a coalition of civil liberties advocates. But the judge may not be inclined to grant the request.

As earlier reported in ACLU Lawsuit Tests Obama Openess Policies, the three memos at issue were written by then-OLC director Steven Bradbury and reportedly authorized abusive interrogations of suspected terrorists and decided that such extreme tactics would not violate the law. The Bush administration repeatedly refused to turn them over, but given President Obama's promises to open government and increase disclosure under FOIA, the Justice Department now is under considerable pressure to change its position and release the documents, which could be critical to any future investigations or prosecutions of Bush officials.

The New York Times reported in October 2007 that the memos provided "explicit authorization to barrage terror suspects with a combination of painful physical and psychological tactics, including head-slapping, simulated drowning and frigid temperatures." These did not, the memos concluded, amount to "cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment" -- which would have been banned by international law, as well as a bill Congress was then considering.

The American Civil Liberties Union, which sued for the memos along with several other organizations, argues the memos don't fall under an exception to FOIA because they constitute adopted policy, not confidential legal advice. Although the ACLU agreed to give the Justice Department some additional time to respond to the request, it argued in court this week that 90 days is too long. The case has already been going on for more than five years.

"The Obama administration deserves credit for its disavowal of torture and for the commitment it has made to transparency, but the public has waited long enough for the disclosure of these memos," said Jameel Jaffer, Director of the ACLU's National Security Project, in a statement released today.

"There is a public debate taking place right now about the role of the CIA going forward and about accountability for the abuses of the last eight years. The immediate release of the memos would allow the public to participate more meaningfully in that debate. While we applaud the administration for its promise of transparency, it's now time to make good on that promise."

On Friday, Judge Hellerstein ordered both sides to appear in his court next Wednesday to discuss how long a delay is warranted. "I take that as a good sign," Jaffer told me Friday. "But we'll see what happens on Wednesday."

|

|

Will the Bush administration be held accountable for war crimes? The answer ought to be yes, if the verdict of the Senate Armed Services Committee Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in US Custody is to mean anything. The bipartisan report, released on December 11 by senators Carl Levin and John McCain, concluded that the torture and abuse of prisoners was the direct result of policies authorized or implemented by senior officials within the current administration, including President George W. Bush, former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld, and Vice President Dick Cheney's former legal counsel (and now chief of staff) David Addington.

Since the scandal of the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq broke in April 2004, over a dozen investigations have identified problems concerning the treatment of prisoners in Iraq, Afghanistan and Guantanamo, but until now no official report has looked up the chain of command to blame senior officials for authorizing torture and instigating abusive policies. The Bush administration has been able to maintain, as it did in the wake of the Abu Ghraib scandal, that any abuse was the result of the rogue activities of "a few bad apples."

This is now untenable. As the report states: "The abuse of detainees in US custody cannot simply be attributed to the actions of 'a few bad apples' acting on their own. The fact is that senior officials in the United States government solicited information on how to use aggressive techniques, redefined the law to create the appearance of their legality, and authorized their use against detainees. Those efforts damaged our ability to collect accurate intelligence that could save lives, strengthened the hand of our enemies, and compromised our moral authority."

Though containing little new information, the report is damning in its revelation of how senior officials sought out and approved the reverse engineering of techniques taught in the US military's SERE schools (Survival, Evasion, Resistance, Escape) for use on prisoners captured in the "war on terror." These include "stripping detainees of their clothing, placing them in stress positions, putting hoods over their heads, disrupting their sleep, treating them like animals, subjecting them to loud music and flashing lights, and exposing them to extreme temperatures." In some circumstances, the measures also included waterboarding, a notorious torture technique which involves controlled drowning.

After noting that these techniques were taught to train personnel "to withstand interrogation techniques considered illegal under the Geneva Conventions," and that they are "based, in part, on Chinese Communist techniques used during the Korean war to elicit false confessions," the authors laid out a compelling timeline for the introduction of the techniques, beginning with a crucial memorandum issued by Bush on February 7, 2002. This stated that the protections of the Geneva Conventions, which the authors noted "would have afforded minimum standards for humane treatment," did not apply to prisoners seized in the "war on terror."

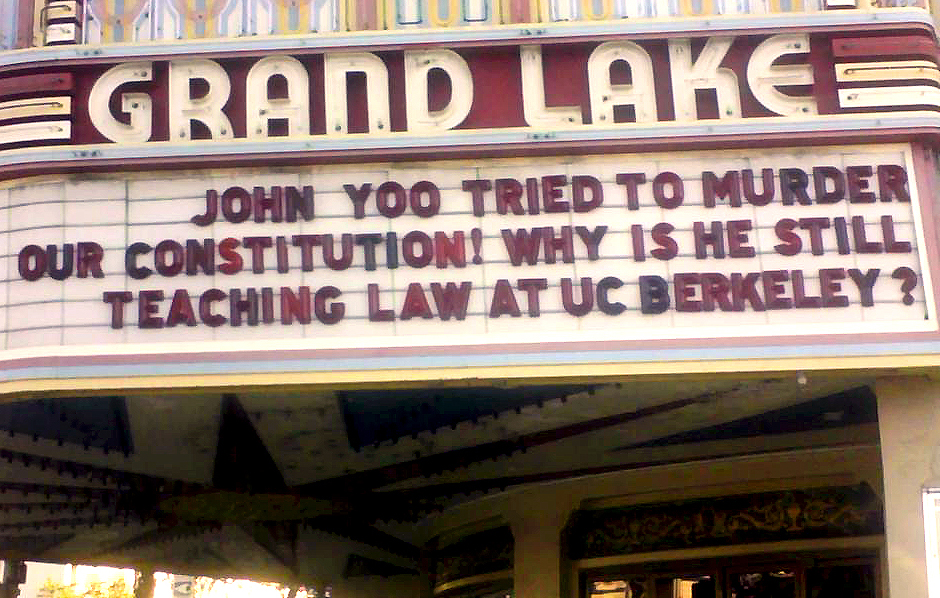

Having

established Bush's role as the initial facilitator of abuse, the report

then implicated those directly responsible for implementing torture,

explaining how Pentagon general counsel William J. Haynes II began

soliciting advice from the agency responsible for SERE techniques in

December 2001, and how Addington, Justice Department legal adviser John

Yoo, and White House counsel Alberto Gonzales attempted to redefine

torture in the notorious "Torture Memo" of August 2002. The memo

claimed that the pain endured "must be equivalent to the pain

accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment

of bodily function, or even death."

The authors also noted how Rumsfeld approved the use of SERE techniques at Guantanamo in December 2002 (after Haynes had consulted with other senior officials), and explained how the techniques migrated to Afghanistan in January 2003, and were implemented by Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, the commander of coalition forces in Iraq, in September 2003.

Even so, the report is not without its faults. The authors carefully refrained from ever using the words "torture" or "war crimes," which is a considerable semantic achievement, but one that does little to foster a belief that the officials involved will one day be held accountable for their crimes. They also, curiously, omitted all mention of Vice President Dick Cheney, and ignored the importance of the presidential order of November 2001, which authorized the capture and indefinite detention of "enemy combatants," even though Barton Gellman of The Washington Post has established that Cheney played a significant role in this and all the other crucial documents that led to the torture and abuse of detainees.

Responses in the US media have been mixed. Oddly, most major media outlets chose to focus solely on Rumsfeld's responsibility for implementing abusive techniques. More thoughtful commentators have questioned whether Barack Obama would pursue those responsible, noting that he will be unwilling to antagonize Republicans, whose support he needs to tackle the economic crisis, and that many Democrats in Congress knew about the administration's policies, and in some cases were involved in approving them. A recent article in The Nation noted that such complicity made "an unfettered review seem unlikely," but the article also noted, more hopefully: "A growing body of legal opinion holds that Obama will have a duty to investigate war crimes allegations and, if they are found to have merit, to prosecute the perpetrators."

As of December 17, those concerned with pursuing Bush administration officials for war crimes can at least be assured that the perpetrators now include Cheney. In an interview with ABC News, the vice president stuck to a now-discredited script, declaring "we don't do torture, we never have," but admitted for the first time that he knew about the use of waterboarding on a handful of "high-value detainees," and that he considered its use in their cases "appropriate."

Only time will tell if Cheney's admission will be regarded as a stalwart defense of national security, or as the last defiant gesture of a war criminal.

Huzaifa Parhat, a fruit peddler, has been imprisoned at Guantánamo Bay Detention Center for the last seven years. He is not a terrorist. He's a mistake, a victim of the war against al Qaeda. An interrogator first told him that the military knew he was not a threat to the United States in 2002. Parhat hoped he would soon be free, reunited with his wife and son in China. Again, in 2003, his captors told him he was innocent. Parhat and 16 other Uighurs, a Muslim ethnic minority group, were living in a camp west of the Chinese border in Afghanistan when the U.S. bombing campaign against the Taliban destroyed the village where they were staying. They fled to Pakistan, but were picked up by bounty hunters to whom the U.S. government had offered $5,000 a head for al Qaeda fighters.

The Uighurs were officially cleared for release in 2004, but they remain at Guantánamo. They cannot be repatriated to China, because they might be tortured, and no other country will take them. The U.S. government does not want to allow them into the United States for fear of setting a precedent that might open the door for detainees it still considers dangerous. In 2006, after again being told that they were innocent, and becoming desperate, some of the Uighurs began mouthing off to their captors. They were sent for a time to Camp Six, a $30-million "supermax" prison for holding al Qaeda suspects in isolated cells.

In the tomb-like confines of this concrete prison, some of them began to crack up, says P. Sabin Willett '79, J.D. '83, a Boston-based attorney with Bingham McCutchen, the firm that has represented the Uighurs pro bono since 2005. "The Department of Defense has studied what happens to human beings when they are left alone in spaces like this for a long time and it is grim," Willett notes. "The North Koreans did this to our airmen in the 1950s. The U.S. ambassador to the United Nations went to the floor of the General Assembly and denounced the practice as a step back to the jungle."

Continue reading The War and the Writ: Habeus Corpus and Security in an Age of Terrorism.